Chronicles about the artistic dissidence

in Cuba

1961 – 2021

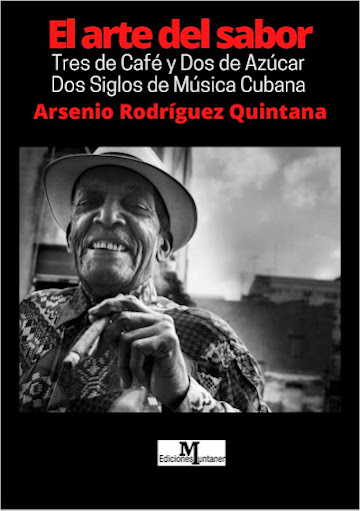

Arsenio Rodríguez Quintana

Translated by Daylin Horruitiner

https://www.amazon.com/-/es/gp/aw/d/B09PHL68FN/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1641114126&sr=1-1

What worries me most is not my death. The

change in Cuba has to be more than a leader or a movement. Every Cuban has to

be a leader and agent of change which is happening already.

@Mov_sanisidro #weareconnected

Luis Manuel Otero

No one is unaware that Spain governs the

island of Cuba with a bloody iron arm, not only does it not leave her security

in her properties, bragging on the right to impose attributes and contributions

as they please, but leaves her deprived of all civil, religious, and political

freedom. Her children are expelled to remote climates or executed without trial

by military commissions established in full to suit the lacking civil power

deprived of the right of assembly, unless under the presidency of a military

chief. They cannot ask for a remedy for their ills without being treated as

rebels and given no other recourse than to shut up and obey.

10th of October Manifesto General Chief

Carlos Manuel de Cespedes Manzanillo 1868

...Fears has many eyes

And sees the things under the ground.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

Don Quijote

Introduction

“No one considers me a political writer

nor I consider myself a politician. But it turns out that there are times in

which politics intensely turns into an ethical activity. Or at least in the

motif of an ethical vision of the world, moral motor.”

Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Mea Culpa,

1992

Book content

This book is a gathering of texts that I

wrote while the 16 fearless Cubans were quartered in San Isidro on a thirst and

hunger strike. It also contains declarations, petitions, and messages

from those quartered. I highlight in the 1st Part, the consequences caused

by solidarity from other artists from the island that today are gathered after

27N, name that represents the physical and explicit solidarity of around

four-hundred artists of the same generation, and other of long trajectory like

musicians Carlos Varela, Haydée Milanés, and Leoni; actors and film directors

Jorge Perugorria, Fernando Pérez, Luis Alberto García, Lynn Cruz and some

members of the MSI that planted themselves at the Ministry of Culture to

demand a dialog with the minister to protect the rights of the MSI members as

well as theirs, in a sleepless event that became active history of the artistic

dissidence in Cuba.

There are texts in the 2nd Part, that were

written before November 2020, meaning the last 10 years, which warn that the

bursting of the MSI is just another effect of dissidence, but it’s impact,

thanks to social media, has been greater.

Here is a preliminary view, though not

complete, of important events of the artistic dissidence in the last 60 years

of the Cuban revolution: PM, UMAP, Puente Group, Caso Padilla, Reinaldo Arenas,

Arte Calle, Generación Y, Festival de Rotilla, entre otros. I want

to clarify that this book is not a compilation of the political opposition in

Cuba, that is a job I leave to others, I focus on the artistic

dissidence. I know of the importance during these years of The Ladies in

White, Osvaldo Payá, Orlando Zapata Tamaño o UNPACU, among others, but I

didn’t focus my book in that direction. I also highlight the effects that the quartered

has awakened within Cubans that live out of the island, and how they began

to show ample solidarity by protesting in front of embassies and Cuban

consulates in America and Europe.

Maybe the quartered connected many with

this movement because the MSI has basic premises that others had not planned

before. They don’t want to leave the country (Ileana Hernandez, and Carlos

Manuel Álvarez , two of the 16 quartered, had already lived out of

Cuba, and had returned), they want a new Cuba for all, they are street smart,

and they don’t reject any of the more intellectual collectives, artists or

disciplines, or anyone from the streets who shows solidarity.

Origins of the MSI

The Movimiento San Isidro (MSI)

develops when the current president of Cuba, Miguel Diaz – Canel,

promotes a series of laws that limit the acting and Cuba of Independent

Artists, on his way to a constitutional reform. This mainly activate artists

like Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara who doesn't have academic formation, but

already in 2018 when this reform occurs, had already been widely recognized in

and out of Cuba so as to demand that academic formation isn’t an impediment to

be an artist, one of the new controversial points of the new law. Him and many

artists that live in Cuba have something more important, they have lost fear,

and if someone pursues their rights knowing the consequences and still

persists, any government will have a problem, the Cuban dictatorship

isn't the exception.

The new measurements promoted by

Canel on August of 2018, permit or activate the formation effect on

September of that year. Since that date, the San Isidro Movement led by Luis

Manuel Otero Alcántara, began a series of actions to protest against Decree

349, with a sign reading SIN349 (WITHOUT349), which goes viral on various

platforms of photographers, writers, performing and plastic artists that didn’t

form part of the MSI but shared their ideas. Even though there are other

decrees, this is the one that was emphasized. Spontaneously and peacefully many

join this cause.

What is Decree 349?

En Summary: The new law is an update of

another decree, 266, which dates back to 1997 and regulates the cultural policy

and the “benefit of artistic services”. The transformations of the Cuban

society after the approval of self-employment extended cultural activities

beyond the oficial institutions to ambiguous “public spaces not of the

state”.

Many of these places are vital for the

arts presented on the island today. Galeries and private home theaters, as well

as restaurants with cultural programing, and alternative audiovisual exhibits

have proliferated and are now placed under automatic suspicion. To sum it up,

the law demands the approval of the authorities so that artists can present

their work in public, and creates the inspector character, who can close an

exhibit, or interrupt a concert if it is determined that they are not in

accordance with the Revolutionary cultural policy. Other ambiguous points of

this legal norm is the definition of an artist and up to what point this

requires the need of the artist to register to a state institution.

Miguel Díaz-Canel and the new Minister of

Culture, Alpidio Alonso, were met with the rejection of other renown artists

like Silvio Rodríguez, José Angel Toirac, Luis Alberto García (actor turned

popular influencer), and by internationally known “artivists” like Tania

Brugera, just to name a few.

Now, the ones that in reality showed

continuity in this protest of SIN349 were the MSI: Luis Manuel Otero, Yanelys

Núñez, Amaury Pacheco, Iris Ruiz, Michel Matos, Sándor Perez, Adonis Milán,

writers Javier Moreno and Verónica Vega, and painter Yasser Castellanos. As

expected, and as it has happened in Cuba since 1959, the political police took

matters in their hands and the majority of the artists and others that made

public their opposition of this Decree, suffered the modus operandi of a

repressive regime: threats, absurd arrests, interrogations, and of course the

habitual censorship and informative silence common in these cases.

To cite two examples that surged as a

response to this controversial decree, Luis Manuel Otero, was incarcerated 12

days in March for, according to the authorities, using the flag in an

“outrageous” way, in a performance. Also, rapper Maykel (Osorbo) Castllo, was

condemned to a year in prison in 2018 for “attempt against authority”.

Role of social networks in the dissident

artists:

#estamosconectados #cubanossomostodos

What changes everything in this context is

precisely the aperture of the internet in Cuba, that even with price and

quality limitations, access to this source of information outside of the

official one has been vital to the waking of consciousness of the Cuban people

in and out of the island that had almost always shown itself as passive or

“disconnected” from this reality. What the dissidence demonstrates is that

prior artistic movements weren’t successful not because they were worth less,

but because of lack of awareness and official misinformation.

It’s no coincidence that the phrase or

hashtag preferred by the MSI is #estamosconectados (#weareconnected).

The role of social networks has been vital

in promoting and gathering support to the MSI in and out of Cuba. From

YouTubers like Otaola, the most popular one, who says he focuses on “gossip”,

but his channel is as political and social as Eliecer Avila, who exclusively

dedicates his platform to political dissidence. Without a doubt, live

transmission gathers great attention since they reach anywhere from two to

three thousand views during the live broadcast. People not only connect, but

they share, and that has made this phenomenon of MSI a media addiction

resembling a reality show where the MSI has a lead role and the political

police has the second, and media like youtubers, Facebook pages and digital

magazines have another. All this leads to the negative campaigns by Granma,

Juventud Rebelde and Cuban TV, including their round table, to be fact

checked and discredited.

Parallel to this opposition to SIN349,

several digital publications that were born between 2014 and 2016 were

consolidated; Periodismo de Barrio (2015), Cachivache Media

(2016-2017), 14ymedio (2014), Cibercuba (2014), El Estornudo

(2016) (his director, Carlos Manuel Álvarez is quartered for two days in

San Isidro), El Toque (2014), Hypermedia Magazine (2016), Negolution

(2016), PlayOff (2015), Postdata (2016) 1. As can be seen, almost all of them were

created as of 2014, directed and written by young journalists that live the

Cuban reality and have lost all sense of fear and censorship even with

consequences of surveillance and arrests. In the case of Luz Escobar, or Mónica

Baró, recognized outside of Cuba for her journalistic labor, are illustrative,

though there are many others. All of them have supported the quartered.

This echo on social media caused by these

publications has support directly from outside of Cuba, and from digital

magazines already existing out of the island. Diario de Cuba o Puente

a la Vista, are directed by people that haven’t lived there for a long

period of time, they are triggered by this and their echo in one way or another

wakes up the solidarity of Cubans abroad that usually don’t support this type

of project due to fear of repression that would affect their yearly vacation

visits from Europe or the United States.

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and the rest

of the quartered are conscious for the first time of the strength that needs to

back up the digital press created by Cubans outside of Cuba, and also the press

in Spain. Miami has historically supported every protest of Cuban opposition

without any doubt, that’s why to highlight that Spain, and other cities in the

U.S. and Europe also offer their support adds a greater or distinct

value.

It also debunks the Cuban government

thesis that the opposition is nothing but agents paid by the CIA, or

mercenaries, because who then pays the writers and Cubans exiled in Europe that

sympathize with the quartered of San Isidro, the FBI? The element of support to

these dissident artists given by BBC, France24, and EuroNews, debunks

any conspiracy theory of the Cuban revolution.

The right wing newspapers in Spain as well

as the progressives (calling El País leftist is a joke) follow closely

everything that happens to the San Isidro quartered in the past two years, and

without a doubt the Cuban political police, and its leader Fernando Rojas, are

fully aware of this. That’s why the detentions of Luis Manuel become visits to

the station, always unpleasant, but not like how it was when this viral

visibility didn’t exist on social media.

The cause that propels the quartered to

plant themselves

On November 9th, 2020. Denis Solís,

publishes a video where a Cuban police officer takes the liberty of entering

his home without consent to issue a citation. The virality of this video on

social media provoked at first the empathy of many and the rejection of a few.

Maybe because arbitration in Cuba has been in place since 62 years ago, and

many people see it as “normal” that a police officer invades their home without

permission, arrest order, or any ID, and violates your right to intimacy and

the normal thing is to remain quiet.

Denis Solís, insults this police officer

and kicks him out of the house with a language truly profane, surely the same

any Cuban would have used to expel an intruder from their home, that is if they

didn’t physically attack them first.

His language, and not the violation of

private space on behalf of the police officer, is the excuse of MSI detractors

to not empathize with Denis, without realizing that violating rights, which is

habitual, is the cause of the altercation, and not the language.

When Denis Solís is arrested, Luis Manuel

Otero Alcántara and other civilians quartered themselves in his home located at

Damas 955 (MSI headquarters) to ask for the liberation of Denis Solís.

On the 17th of november 2020, the San

Isidro Movement summoned to a "poetic whisper" in Old Havana to

demand the immediate release of rapper Denis Solís González, activist of the

group that was unjustly incarcerated for expressing his political ideas.

"The habaneros (people from Havana) are invited to accompany us at the

headquarters of the movement, located in Damas 955 between San Isidro and

Avenida del Puerto", they wrote. "Here we will be for several days, a

group of artists and friends, sharing our favorite works, singing, acting and

imagining a more fulfilling Cuba for all. We want all those who understand that

by demanding the release of Denis, we are demanding our own freedom as well, to

be a part of poetic whisper."

Being surrounded by the political police

at Damas 955 in Old Havana, San Isidro corner, and after having food

intercepted, nine of the 15 members of the group began a hunger strike on

November 18th. There were only three members of the San Isidro Movement

involved in the hunger strike: Luis Manuel Otero, Maykel Osorbo, and Yasser

Castellano. The remaining thirteen were civilians that ranged from poets to

housewives or self-employed individuals.

A few days later, on November 26th, after

several episodes of oficialist terrorism, the movement headquarters was

assaulted by agents of State Security disguised as pulic health workers, and

the strike participants and their friends were arrested and separated. Luis

Manuel Otero was not allowed to return to his home, and even though he was not

officially incarcerated, he can't go back, somewhat of a semi-kidnapping

situation. This happens to Tania Bruguera as well, even though she was not

within the quartered.

All social media in Cuba was disconnected

prior to the assault. Electricity was also disconnected to prevent the filming

or photographs of the assault that eventually

surfaced.

Something like this had never happened in

another generation. They are dissidents, artists and you can say politicians at

the same time. One of these concepts is not bigger than the other. They carry

the seed of change, and they have engraved on their skin that we are all Cuba.

When Mick Jagger, in his historic concert

in Havana in 2015 asked Cubans: “Things are changing in Cuba, right? And

everyone responded “Yessss”, maybe not everyone was conscious of this, but

it's probable that something began to circulate in that moment that was

embedded in the collective memory of a generation that has started change, and

The San Isidro Movement is only phase one.

The purpose of this book is not to reflect

a success, it is to leave a photograph of an event that has greatly impacted artists

and Cubans that live on the island and don't have ties to art outside of

Cuba.

He who believes that the government

admitting its dissidence is a success is fooling themselves. Opposition exists

in every democratic country, that is normal. In Cuba is only a step after sixty

years without movement; the success will come when people can have free

elections with the parties presented, and control is no longer fully in the

hands of the state.

Getting the government to tolerate

dissidence is not common, that's why this book should serve as a warning not to

fall for a trap of promises that won't lead to full freedom of rights. The

change can be a reality if everyone gets on board leaving personal desires for

the common good including those who have a different way of thinking.

That ethical motor that is today

represented by the quartered in San Isidro, took me to gather my ideas of

artistic dissidence in Cuba on these pages. I hope that most will see the

composition of links that always lead to plant new rights and liberties.

Arsenio Rodríguez Quintana

Sant Cugat del Vallés, Barcelona, 2020

1. Almost all emerging Cuban media has been the subject of threats or any other form of intimidation. Some journalists living in Cuba have been interrogated by the Department of State Security, and others have been harassed on social media by false or anonymous profiles. Elaine Díaz, Blogger, January 11, 2018.